Publishing regulatory compliance data as open linked data improved engagement while reducing costs

In 1957, six year old Caroline Wakefield died of polio contracted from raw sewage discharged into the sea near Stokes Bay in the Solent. In response, her father Tony set up the Coastal Anti-Pollution League to share information about coastal pollution, and campaign for change. Since then, the waters we swim and play in have become much cleaner and much safer. Designated bathing waters are monitored throughout the summer season. But until recently, it was hard for the public to find out just how clean, or not, the seas around our beaches are.

Starting in 2010, the Environment Agency, and subsequently Natural Resources Wales, have made all of that bathing water quality data open to anyone to use. They have tried to make it easy to use, not just downloadable to a spreadsheet. Their hope has always been that opening up their data in this way will drive progress towards even cleaner bathing waters, and also lead to the discovery of new and creative applications of the data.

Introduction

We all want the waters that we swim in, at the beach or inland, to be clean. In England, responsibility for collecting data about the cleanliness – or otherwise – of designated bathing water sites falls to the Environment Agency (EA). In Wales, it falls to Natural Resources Wales (NRW). EA and NRW collect bacterial concentration and other data, and determine whether each site is in compliance with the European Bathing Water Directive. That data is reported annually to the European Commission, but before 2011 it was not routinely shared online with members of the public. The data was shared with partner organisations, such as water companies, local authorities and environmental charities, but the workflows for doing so were often slow and unwieldy.

In 2011, EA were keen to explore releasing data collected with public funds to the public. EA, which at the time also had responsibility for Wales, took a decision to publish water quality data freely and openly: no charge would be made for accessing the data, and the terms of the Open Government License imposed few restrictions on its use. Since then, this project has been extremely successful. The public have access to important water quality information as it is collected, and can make better-informed decisions about where it is safe to swim or go into the water. Partner organisations, such as local authorities and environmental charities, can incorporate live data into their workflows with no delays and without requiring specialist IT capabilities. For the data publishing agencies, EA and NRW, delivering these benefits has actually been cheaper than the previous manual processes. Perhaps most interestingly, the choice of linked data as a basis for the data service has proved very flexible: additional datasets and application services have been added over the lifetime of the project, without any fundamental redesign of the underlying technology.

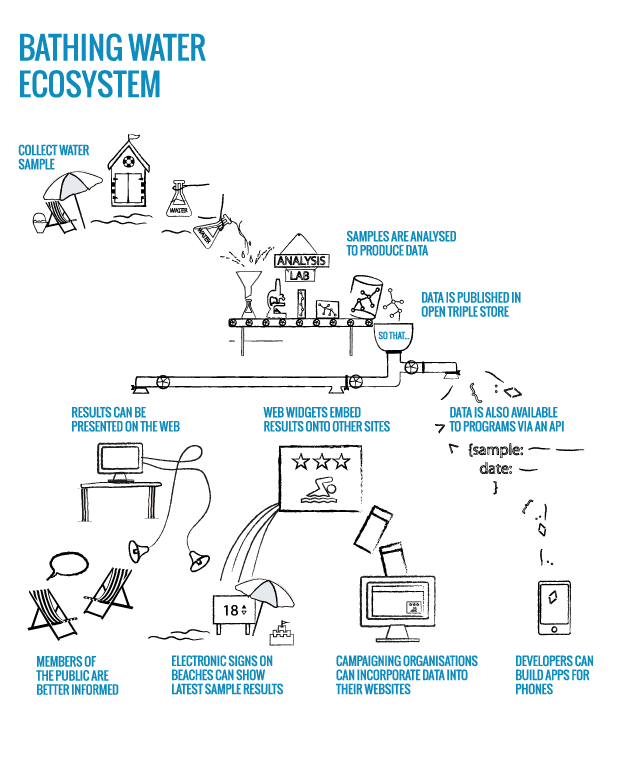

Epimorphics has been the key delivery partner throughout this ongoing project. From the initial pilot project to managing the cloud service hosting the data, we have seen this dataset grow from an experiment in open data publishing to a critical component of water quality information delivery for a growing number of data consumers. Our experience has been that simply making the data available would not have been enough to get the environmental and business outcomes that EA and NRW were seeking. Rather, we have supported the data with a growing range of applications, services and educational resources. We wanted, though, to validate this experience. The Summer Showcase provided a timely opportunity to engage in some user-centered research to find out how open bathing water data has been used, to understand the overall ecosystem, and to determine some the factors that were key in building up to the picture we see today.

Bathing water data in-use

As the bathing water data project has gone on, the data that is put out has grown. At its heart, however, are two central datasets: weekly sample readings, and annual classifications. The processes for collecting and interpreting each dataset are governed by the European Bathing Water Directive. Essentially, each week from May to September, a sampler goes to each of the designated bathing water sites (417 in England and 102 in Wales) and collects samples of the water. These samples are analyzed in the lab, to determine the concentration of two specific species of bacteria – both of which to some degree are harmful to human health. The lower the concentration of bacteria, the cleaner the water. The more sewage there is, the more bacteria show up.

The most robust indicator of the quality of the bathing water is derived from a statistical analysis of these bacteria counts over a four-year window, and is calculated once-per-year after the final sample is collected in September. This produces the bathing water’s annual classification, on a scale from poor, through sufficient and good, to excellent. Water users can be confident that bathing waters that are classified as good or excellent carry minimal risk of causing illness. Bathing waters classified as poor are likely to be targets for investment to improve the water quality.

In addition to publishing these annual classifications, EA and NRW also publish the underlying sample data. In statistical terms, these readings form a “hypercube”: for each bathing water site, for each week of the season, and for each of the two types of bacteria, there is a single number indicating the amount of bacteria per 100ml of water. As soon as this most up-to-date result is available from the lab, it is published via the linked data feed.

Benefits

The Data Publishers’ Story: the Environment Agency and Natural Resources Wales

As part of their statutory duty, EA and NRW are required to publish each year a profile of each bathing water site. These used to be PDF documents, taking several weeks to prepare each year. Updating the profiles mid-way through the bathing water season could not happen. Relating profiles to sample results was a manual process. By publishing the bathing water profiles as data, and using that data to drive the web presentation, the agencies could replace a slow, expensive process with a responsive automated site, saving time and money while also providing a better service. They can meet their statutory reporting requirements more efficiently and effectively.

… the most impressive thing is the way it has extended the reach of our data, via widgets and the API, into other peoples’ websites. The improved transparency has really helped us in developing partnerships

Tom Guilbert, Environment Agency

While some water quality information had been available through older systems, both EA and NRW found that Freedom of Information requests were widely used by individuals and organisations to gain access to data. Typical requests might include ‘What is the water quality at this beach?’ or ‘Give me all of the bacterial sample data for this set of beaches for the last season’. Responding to FoI requests on a case-by-case basis was slow and expensive. Since the publication of the bathing water data, both agencies reported a significant reduction in FoI requests. Moreover, many of the residual requests can be answered by directing enquirers to the open data site.

We have also been able to reduce the time and effort we put into publication and sharing information with local authorities and FOI requesters. Some of this time we have reinvested in making more frequent publications (i.e. daily in-season sample uploads), the rest can be used locally on building partnerships and implementing projects to improve water quality.

Tom Guilbert, Environment Agency

Increasingly EA and NRW work in close collaboration with other stakeholders, including local authorities, charities and other NGOs, beach managers, tourist organizations and water companies. Historically access to bathing water quality data has often been a point of friction between the agencies and their partners and stakeholders. Reasons included the time taken for busy staff to collate information from multiple data sources in different formats. Making data readily and easily available has improved transparency, trust and collaborative working.

Both agencies reported that their own staff, who do have access to internal systems, often use the external linked-data site simply because the information is integrated and convenient. NRW have also used the linked data feed in a development exercise in mobile app development as part of their internship programme, and to make the data more easily accessible to Welsh speakers.

Linked-data has helped us meet our Welsh-language requirements. The flexibility of the data made building a Welsh-language version of the widget a straightforward task.

Dave Johnston, Natural Resources Wales

The Bathing Water Managers’ Story

Some bathing water managers are only responsible for one location; others, including many local authorities, look after several.

More than forty local authorities host the bathing water widget on their web site. The widget is a simple, cost-effective way to embed water quality information into a web page. During August 2015, the widget was viewed more than twelve thousand times on local authority web sites alone. Local authorities view the bathing water information as useful both to local residents and to tourists.

The [local survey] results confirmed that providing bathing water quality information is extremely important to locals and visitors alike, even if they are not likely to swim or take part in watersports.

Sam Naylor, Swansea Council Housing and Public Protection Team

Often, pages describing an authority’s beaches are maintained by officers who are not I.T. specialists or web developers, typically in an environmental protection or tourism and leisure department. Including the widget does not require any specialist I.T. knowledge. It provides local people and visitors with authoritative, up-to-date water quality information without straining I.T. budgets and resources.

In local authorities too, internal information requests and external freedom of information requests can consume considerable time and resources. Providing self-service data reduces the numbers of requests for information. Swansea Council noted that the Cultural Services department, responsible for the beach award schemes, no longer had to go to the Housing and Public Protection team for data, freeing up time and resource on both sides.

The sooner bathing water managers know about problems, the sooner they can take action to address them. Once sample results, pollution predictions or abnormal situation are entered into the triple store, they are available to everyone. Even smaller organisations, such as the Henleaze Swimming Club in Bristol (whose swimming lake is a designated site), can monitor the water quality results and anticipate problems. Having authoritative data is important; they noted “unless you’ve got data it’s all people’s opinion and hearsay”. Timely and live data support faster and more effective decision making.

Campaigning Organisations’ Stories

Surfers Against Sewage, the Marine Conservation Society and other environmental charities and NGOs have long campaigned to have detailed bathing water quality data made openly and transparently available. Internally, they use the data for their own scientific analysis and trend-monitoring, to organise and campaign for remedial action and to hold water companies and the environmental agencies to account.

Surfers Against Sewage produce a popular website and mobile phone app which alerts surfers and other beach users to poor water conditions. This application combines pollution warnings from EA and NRW with sewer overflow alerts from water companies. At present this is the only service that provides a combined view of both sets of data feeds in real-time across England and Wales.

The Marine Conservation Society’s Good Beach Guide combines the society’s own information sources with water quality data via the API and the widget service into an integrated guide to beach quality. Other coastal organisations, including RNLI and LOVEmyBEACH, add data from the API or water quality widgets to their own information web sites. Providing authoritative data, openly licensed, in a way that can easily be incorporated into an organisation’s own website or mobile app means that combining information sources to better meet end-user needs is easier and cheaper and need not require specialist I.T. skills.

Marine Conservation Society staff have in the past had to spend significant time processing data delivered to them by the environmental agencies in different formats and at different times. Being able to get data straightforwardly on-demand frees up resources, so that staff can devote more effort to organising, campaigning and community activities.

Community Benefits

All of our interviewees agreed that one of the main beneficial outcomes of opening the bathing water data is that the public can make better informed decisions about swimming or other water sports at bathing waters. Other beneficiaries include journalists gaining additional insight or evidence for their reports, marine researchers getting easier access to source data, and students having a source of inspiration and material for school or college projects.

Extending the data: profiles, forecasts and abnormal situations

When first published, the dataset contained only weekly sample readings and annual classifications. Bathing water profiles are descriptions of each site, containing useful information ranging from the relevant local authority or council and year of designation, to a description of the site. Publishing these profiles is a requirement of the Bathing Water Directive. It used to be a labour-intensive process to pull together the descriptions as a set of PDF documents, which were then not updated during the year. Extending the linked-data description to include the bathing water profiles meant that the water quality data and profile could be integrated into one place, that updates could be made whenever there was a change, and that the process overall became faster, easier and much cheaper to run.

A second extension to the dataset was added to record abnormal situations. These occur when an event interrupts the normal process of monitoring water quality: for example building works disrupt a sewer pipe, or a landslip prevents access to a beach. It is important to notify the public that such events have occurred, so the linked-data data model was extended to describe such abnormal situations.

Most recently, the dataset has been extended to deliver forecasts of short-term pollution. Heavy rain can often cause problems with water quality, as animal waste washes down from the catchment or sewer systems overflow. Combining weather forecasts with hydrological models allows the agency to predict the possibility of short-term pollution events in around a quarter of the currently designated bathing waters. Delivering these daily pollution risk forecasts was another incremental extension to the open data model.

All of these extensions to the linked data model were delivered without disrupting existing published data or the services using it.

An ecosystem of applications and services

Making data available is only a first step. We need to provide additional support to help people to understand and use our data. This can take many forms; in the case of the bathing water quality data we built a developer-friendly API, with extensive documentation, a web site oriented to the end-users of the data, and a widget service. We’ve also taught training classes using the bathing water data, and supported third-party developers to build mobile apps.

The “end-user” of the data has its own nuances. Ultimately, it is members of the public who may want to know if a given site has clean water before booking a holiday or deciding to spend a day on the beach. But other direct consumers of the EA and NRW data include beach managers, such as a local authority or private company, who may want to put up warning signs in the case of a forecast of elevated pollution risk, or charitable organisations campaigning for better water quality across a range of sites. Developing the web site has been an iterative process, taking-in user feedback over time. Throughout, the basic premise has been that the user experience is data-driven: all of the information presented is taken from the underlying linked-data, integrating the additional datasets, such as bathing water profiles and short-term pollution forecasts, as they become available. This has been sufficiently successful that the linked-data web pages are now the official presentation of the bathing water profiles: generating annual PDF documents is no longer done, saving considerable time and money.

Opening up the data

What does it mean to really make a dataset open? It’s more than just the mechanics of computers and people getting hold of the numbers, although that is important. Firstly, users have to understand under what terms they can use the data. Open data means not only that there is no price charged for accessing the information, but also that few restrictions are placed on the uses to which the data are put. In particular, users are permitted to re-use the data in applications and data visualisations, and to combine it with other data sources. In the UK, public sector bodies often use the Open Government License (OGL) to define the terms under which data is licensed. All of the bathing water quality data is licensed under the OGL.

The next consideration is ensuring that the data is understandable and trustworthy. While documentation is always helpful, linked-data has some particular advantages. Every named constant name in a linked-data set is a web identifier, or URI. This means that putting the URI into a web browser, or fetching it with a script, returns a description of that named thing. This sounds slightly arcane, but is actually very powerful. Any terms that are not immediately understandable can simply be looked up, using the well-understood mechanism that drives the world wide web. Moreover the description can include links to provenance information: who published the data, and when? This is essential to show that datasets are transparent and trustable.

Timeline

Success factors

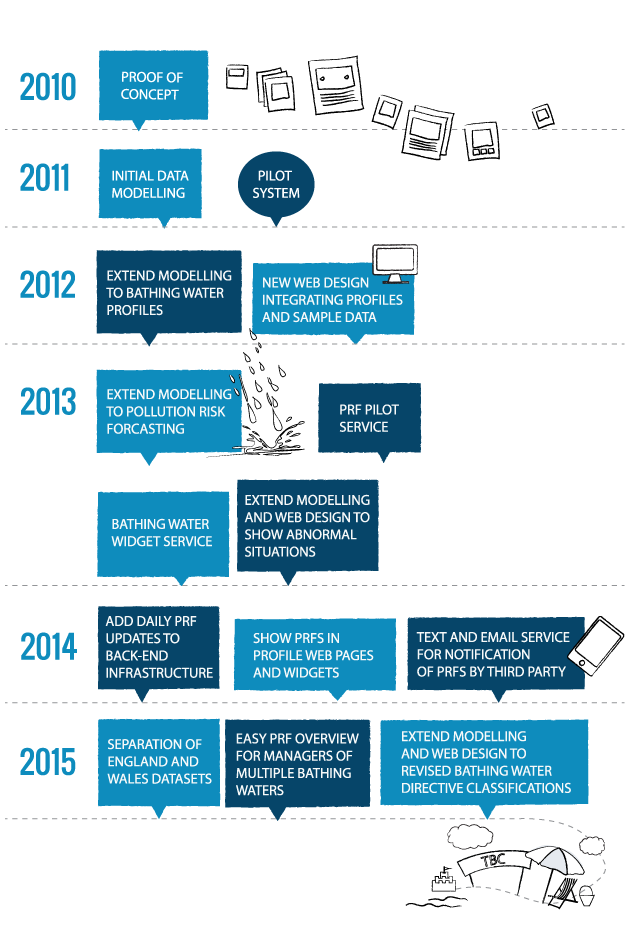

There were many contributing factors to the overall success of this project. We’ll mention just two: iteration and some of the initial data modelling design choices. As the timeline shows, this dataset and the user interfaces presenting it have grown and changed over time. At each point, feedback from users and internal stakeholders was key to refining the design. That iterative approach was made easier by the open, schema-less nature of linked data. Even so, we found that having a carefully chosen set of design principles for how items in the dataset – bathing waters, sampling points, samples, and vocabulary terms – were assigned web identifiers or URIs was very helpful.

Conclusions

EA and NRW will continue to develop and extend the bathing water services based on user needs and legislative changes. EA also intend to publish more open linked data, including water quality readings for inland waters, including rivers and lakes.

If you would like to use this data to build an application or data visualisation, please see the dataset guides for England and for Wales. If you’d like to discuss other uses, or to explore publishing other datasets, please get in touch.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the ODI for their support for the production of this report as part of their 2015 Summer Showcase programme.